A Quiet Launch for a Big Fix: Hinesburg's New Wastewater Plant Has Gone Live

A Special Report: The town's new state-of-the-art wastewater treatment plant has completed extensive testing and is now operational, the culmination of years of work.

By Geoffrey Gevalt

Record Managing Editor

There was no fanfare, no parades or ribbon cutting. In fact, there was no notice at all save a brief mention by Town Manager Todd Odit in his report to the selectboard last month: The new wastewater plant was up and running and fully operational.

It was seven years in the making, took more than four years to build, required a town bond vote and several key state and federal grants to finance and a whole lot of expertise to do it right. After a month of testing without any major problems, Hinesburg’s sewage plant is discharging water that is vastly cleaner than what it had been discharging for decades.

“It is the largest infrastructure project that the town has ever done,” said selectboard member Paul Lamberson. “It’s big news. It deserves recognition.”

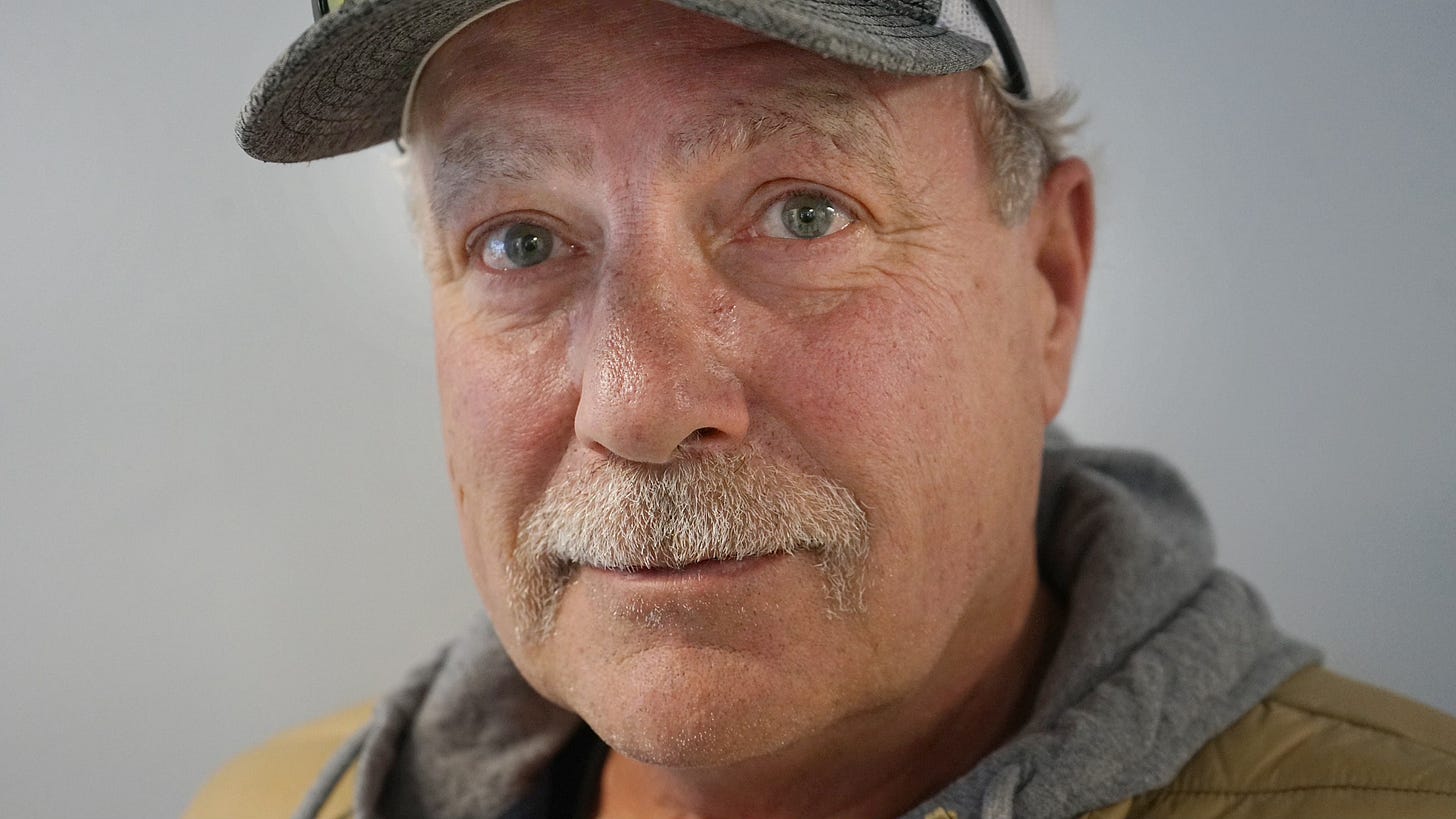

The Record was recently given a tour of the new plant led by Jay Olmstead of Aldrich & Elliott, who has overseen the engineering of the plant for the last four years; John Alexander, assistant chief operator of the plant; and Odit. (Mark Lund is the other Hinesburg employee who, like Alexander, is fully certified to run the plant. Olmstead works for Aldrich and will be returning home to Hanover, NH, in the next month.)

It may seem hard to get excited about a wastewater plant, but Alexander’s enthusiasm is hard to miss. “I love this job,” he said at one point. “I want to finish out my career here.” The enthusiasm, he explains, is because of how the plant works and how the plant is slowly doing a better and better job of producing discharged water that is far cleaner than the town could ever get with the old lagoons.

To understand exactly what this plant does – versus how Hinesburg used to treat its waste – requires a science degree. Here’s the simple version:

The old plant

The way Hinesburg used to treat its sewage is a bit startling when you think about it. There were four open lagoons. Sewage (or ‘influent’ as it’s called) was loaded into the first lagoon where the solids began to settle and bacteria began breaking them down. As the solids settled, the wastewater at the top flowed from one lagoon to the next and the next where the process was repeated: solids settled and bacteria did their work. In the fourth lagoon, alum was added to accelerate the final settling.

The remaining liquid was chlorinated and then de-chlorinated and discharged, finding its way to the LaPlatte River and then into Lake Champlain.

In 2018, the state brought the hammer down on the Hinesburg plant saying it was contributing to the pollution of the LaPlatte and Lake Champlain. They issued a discharge permit that required the town to invest in a new plant to drastically reduce the contaminants in the discharge, particularly phosphorous and ammonia. The deadline was October 2026.

At the time, there was another force at work in town: several major housing developments were finally nearing the end of their long, winding permitting processes. More housing – and more waste – was on its way, so Hinesburg needed more capacity as well.

For a while, the town had a prohibition on new development as a result.

The construction

In 2019, the town took the first steps by hiring Aldrich & Elliott to design the new plant. The first problem was the discovery that 60 feet under the first lagoon – where the plant would be built – was wet clay. That was unsuitable for building. So the town paid close to $2 million for Munson Earth Moving to remove the sludge, put it through a centrifuge to remove the water and truck away the remains – dirt and compost.

PVC pipes – wick drains, as they were called – were then inserted into the wet clay to draw out the water as tons upon tons of sand were brought in and dumped on top of the clay to squeeze the water out it. It was a long process, but finally the ground was solid enough to support the new plant.

In the fall of 2020 the town put to the voters an $11.7 million bond issue to pay for construction of the new plant. It passed. Designs were completed by early 2023 when the project was put out to bid But the lowest bid came in at more than $15 million, well over what the voters had authorized.

Back to Aldrich & Elliott: engineers made alterations and the project was again put out to bid. In early 2024, Naylor and Breen came in lowest with a bid of $12.5 million. Work began that spring.

Odit, meanwhile, pressed hard to secure nearly $9 million in federal and state grants, loan forgiveness programs and borrowing to cover both necessary cash flow during construction as well as the full cost of the project, now estimated to be nearly $19 million. This includes the final phase which is the dealing with the remaining old lagoons which will be emptied, filled with soil and restored as natural wetlands later this year.

The new plant

Technically, the new plant works on a similar theory as the old: put the effluent in holding tanks, add alum, mix and aerate, let settle, filter, treat, discharge. But the difference is what is discharged. While not potable water, it is chlorine free, bacteria free and contains drastically lower levels of phosphorous and ammonia. The month-long testing established that the discharge was significantly better than before and was consistently improved as the plant – which relies on precision as well as bacteria – broke itself in. “It’s better every day,” Alexander said.

While a similar theory, a very different outcome and method.

To begin, there are two open concrete tanks that collect ‘influent’, lagoons if you will, where the waste is treated with alum, aerated, mixed and then, when the solids have settled, the water at the top is piped (‘decanted’) into the plant for filtration and eventual decontamination via ultraviolet light before being discharged. No chlorine. Little phosphate or ammonia.

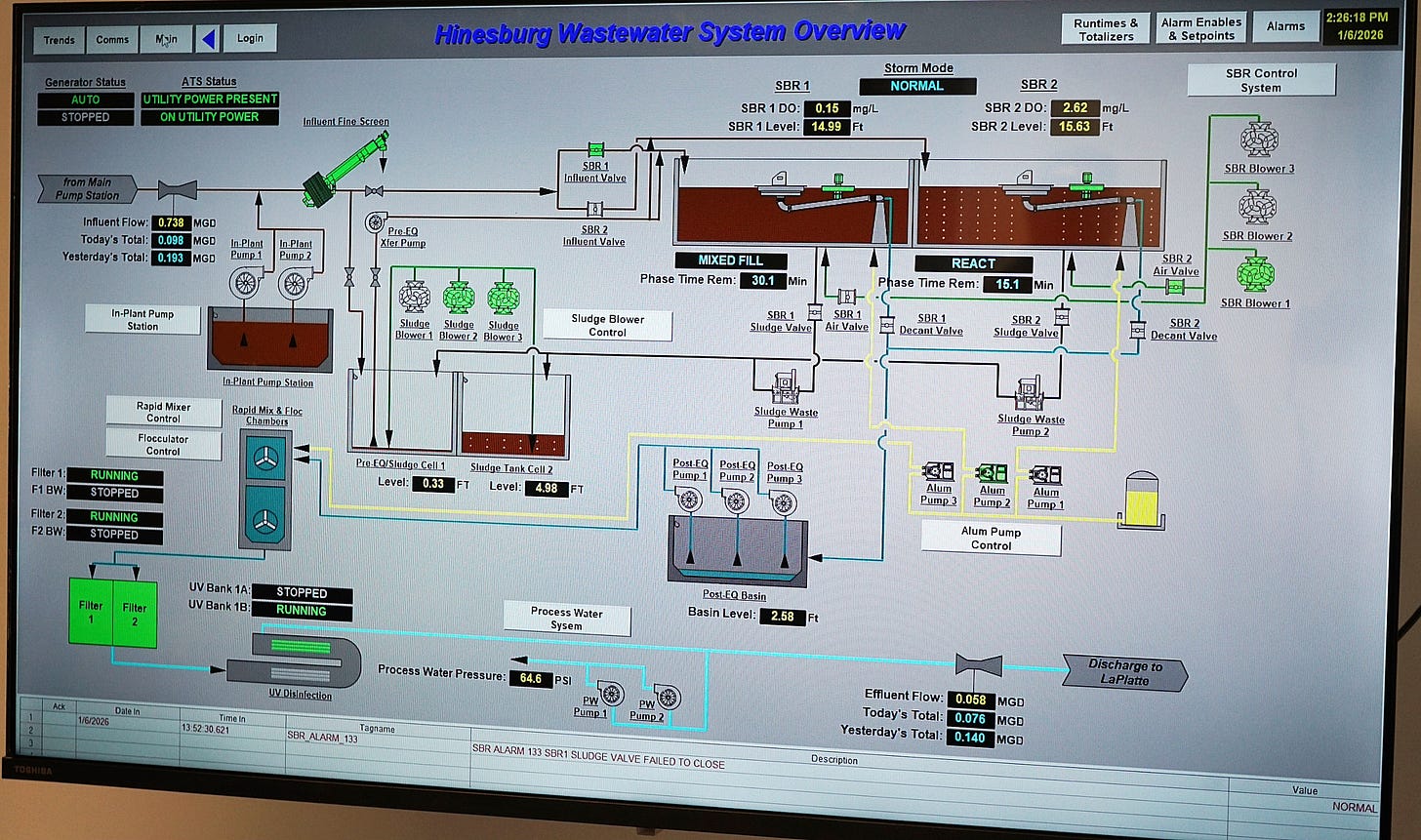

As you can see from the pictures, there’s not much to see. Much of the system is enclosed so there is little odor. Testing is done every day at various times and major tests are done at various stages of the operation – a requirement within the state’s discharge permit. All of this is computerized – except the testing of the water; if there is a problem, the computer lets the operators know.

Each stage, each process is closely timed and looking at the large computer monitor in the two main offices at the plant, operators know immediately what is happening, how much time is left in each holding tank and in each stage.

In terms of capacity, the plant is currently handling about 190,000 gallons per day; it has the capacity for 325,000. The old lagoon system maxed out at 250,000 gallons a day.

The plant still has to get final approvals from the state, but neither Alexander nor Olmstead is concerned in the least. As of Jan. 7, the plant had been operating for 37 days and each day the test results were improved and were well within the state limits on literally dozens of chemicals and contaminants that are tested. The next major full test of the discharge water will be in early February.

The cost

Odit has managed to garner $9.4 million in grants to reduce the amount of borrowing the project would need. He explained the debt financing authorized by the bond issue: “We have a $9.3 million 30-year loan with zero percent interest. Annual debt service on that is $247,479.” However, the first payment will not be due until a year from now.

Ultimately the users bear the cost with higher rates. Currently there are 675 customers that range from small townhouses to CVU (which pays $26,000 a year), HCS ($7,500) and Vermont Smoke & Cure ($36,000).

Ratepayers have groused at the costs. One developer complained at a recent hearing before the Development Review Board that Hinesburg’s charges for water and sewer were “exorbitant” and vastly more than other communities.

Odit and Alexander remind, however, that the town has had no choice in this. The state mandated that it fix an antiquated system that was polluting streams and the lake. At the same time, Odit is aware that to ease the rate burden, the system needs more users.

And the rate base is about to expand. Triple LLL Mobile Home Park on the Richmond Road will be adding 47 users early this year. Construction of hundreds of new housing units will begin this spring and that will bring connection fees from developers as well as hundreds of new ratepayers to spread out the cost.

In a growing community, goes the thinking, the costs for water and sewer will go down, not up. Regardless, the health of the LaPlatte River and Lake Champlain will dramatically improve.

It is really great to have this clear information. Important for us to understand. Thanks.

Thank you for this outstanding article. Like many residents, I dare say, I knew generally about the wastewater issues, but I did not understand the whole process. Todd Odit and the Selectboard deserve credit for their good work.